This is a guest post from the Migration Museum Project.

Well, things don’t always turn out as you’d planned.

We’d always thought it a happy coincidence that Call Me By My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond – the Migration Museum Project exhibition that opened on Thursday 2 June in Shoreditch, London – would coincide with Refugee Week (20–26 June). What we didn’t know, when we gratefully accepted Londonewcastle’s generous offer to have their Project Space rent-free for three weeks, was that our residency would also coincide with the final three weeks of the referendum on Great Britain’s membership of the European Union – a referendum in which the focus has been increasingly on immigration.

Whether this turns out to be a happy or unfortunate coincidence remains to be seen, but the exhibition has certainly given us the opportunity to fulfil one of our main objectives, which is to contribute to a more reasoned debate on migration. A founding principle of the Migration Museum Project is that, as a country, we are unaware of the role that migration has played, and continues to play, in our country’s history and development – and that people on both sides of the debate adopt positions without full information of the facts or the realities. What Sue McAlpine and Aditi Anand (the Migration Museum Project’s curators of this exhibition) have done with Call Me By My Name is to allow people to look beyond the headlines, statistics and abstract language used to discuss the current ‘migration crisis’ and to glimpse into the human experience behind it: how it affects the people involved in it (in this case, residents of the Calais camps, but others, too, whose lives and livelihoods are affected by the camps’ existence) and how people who have endured extreme hardship and travelled immense distances to come to the apparent cul-de-sac of Calais have constructed a settlement there that allows them to hold on to their dignity, humanity and creativity.

The exhibition is constructed across three main spaces, the first dealing with the journeys people have taken to come to Calais, the second looking at the complicated aspect of identity (in a context where revealing your identity may damage your chances of asylum but concealing it can lead to a dangerously corrosive anonymity), the third focusing on the ‘Jungle’ itself – with replications of the dwelling spaces and a large degree of art created by ‘Jungle’ residents: one of the first times that camp residents’ art has been shown to such an extent.

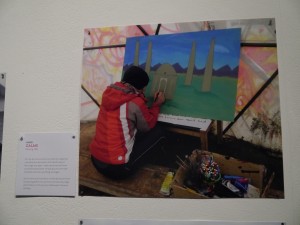

There are stories galore – written, audio and video – and figures that recur in different parts of the exhibition. A photograph shows Habib determinedly painting a picture even as part of the camp is being demolished around him, and the painting’s final version is revealed ten metres away. ALPHA, an artist from Mauritania, features prominently in one of the videos, making a plastic sculpture of the Mayoress of Calais, which is shown in the last room, along with three or four of his other pieces. That room is connected to the others through ‘Un Rideau de Lacrymogène’, a curtain of tear-gas canisters that he created – and a further painting of his, in the second room, reveals his belief that his art can cross borders even if he himself can’t.

ALPHA now has asylum in France but still no passport – so he cannot legally come to Britain, even though not only his artwork has but so too has the house that he lived in until earlier this year (‘La Maison Bleue sur la Colline’ – when the French police evacuated the côté sud of the camp, his house was disassembled and transported to London).

ALPHA’s story is just one of many on display at Call Me By My Name, an exhibition that is guaranteed to make you think differently about our relations with the Calais camps and their residents. Go along and join the debate!

By Andrew Steeds